A tale in which, at 12 and ¾ years of age, I go exploring the South Indian countryside with nothing dependable except a bicycle and my crazy best friend.

I wrote this story when I was 17, for a writing test. My now 31 year old self took the liberty of making some slight edits. 🙂

(please take note that from the ages of 12 – 17 my name was ‘Tulsi Manjari’, as I was given a different name when initiated by a guru and giving a new name to your disciple was the custom. However, around 18 years old I separated from the Vaishnava religion and went back to using my birthname, Jahnavi 😉 )

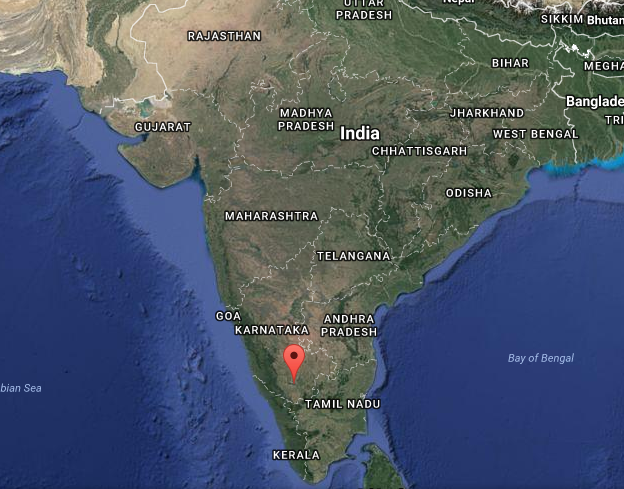

It was 1999, and we lived in Karnataka, India.

Our homes were within a community called Govindaji Gardens (listed as Sri Narashringa Chaitanya Ashram on the map below):

a Vaishnava ashram surrounded by fields of rice and sugarcane.

Between the farm fields around our home were small patches of jungle. Deep in their leafy tangles were hidden ancient shrines and temples, with stones that were worn down and walls that caved in. The whole countryside was riddled with small dirt paths, only traveled by wild dogs and farmers with their cows, buffalo, sheep, and goats.

At the time my best friend was visiting from the U.S. and living at the ashram with us. His name was Radha Kanta, and I always remember him as he was during that time: tall, lanky, loud-mouthed and impulsive.

We had just recently celebrated his 13th birthday and I wasn’t far behind, but he still puffed out his chest and stood tall, importantly reminding that I was younger than him (by about three months).

He and I used to take our bicycles and go for little dusty tours on the few roads we could find. One day, without really thinking much about it, we went off onto one of the small cow-paths, our bicycles rattling noisily on the bumps and rocks. Each path forked off onto at least two or three more obscure paths, and soon we were traveling across a rocky landscape with sparse clumps of bushes, and a few trees whispering loudly around us. The paths began opening up to more and more vast fields of rice and sugar cane. Above our heads, the leaves of coconut and mango trees swished in the breeze, and it was very warm. We saw no one about, and simply pedaled on and on, talking lazily about whatever crossed our minds.

Minutes sped on to make up an hour, and soon we came upon a shady clearing, in which stood two heavy-lidded water buffaloes, chewing demurely on their cuds, and flinging their gray tails at the rude files that gathered at their heels. We bid them a good day, to which their response was a lazy nod of a large, horned head.

A deep well of water was also there, and we peered into it cautiously, wondering, with echoing voices, why it was so big. The circumference around it must have been a good 50 feet, and it was a puzzling piece of architecture to be sure.

But we moved on. After all, buffaloes and water-wells weren’t that exciting.

I admit at that point on our sojourn, I was beginning to worry about where we were, and which path would lead us home.

I said to Radha Kanta, “Shouldn’t we try to head back now?” But I knew he’d want to keep going.

“Well,” he told me, “let’s just go a little more. We can follow this road and see where it goes.”

I grudgingly consented.

The road followed along a large expanse of a rice field, and there, across the swaying heads of the rice plants and streams, we saw the roof of a looming temple, which poked just above the tops of the trees.

Radha Kanta and I stopped our bikes and stood on the road, gazing at it with awe.

“Wow…” one of us murmured.

“Let’s go check that out Tulsi!” Radha Kanta exclaimed. “It looks awesome!”

It looked more forbidding than awesome to me, and there didn’t appear to be any way to reach it except for trudging across the muddy fields. All in all, the temple seemed to be far out of the way.

“But…” I protested feebly. “There isn’t even a road! What if we get lost?”

“We can’t get lost!” he cried, with big gesticulations of his long, skinny arms. “We can just go a little ways down that rice field,” he pointed to the murky mess of rice plants and trenches filled with mud water, “and if we don’t make it as far as the temple, we’ll just turn back.”

I looked at him doubtfully.

“If we go over there, there’ll probably be a road that we can follow to get back!” he cried in a last effort to convince me. “Come on!”

So we picked up our bicycles and headed across the fields without looking back. The going was messy and very slow, involving acres of warm, ankle deep mud. After the first rice field came another rice field, followed by a sugarcane field, than yet another rice field. And still, the gray dome of the eery temple loomed just ahead, out of reach.

By this time our enthusiasm had worn down completely, and Radha Kanta was just as worried as I was. And I was very worried. But then, after just one last rice field, we were there. Or almost there. At least there were no more fields left to trudge through.

We pulled our bicyles out of the mud and stopped a moment, to consider how to get through the tangle of weeds and thorn bushes which stood between us and the temple.

I don’t know how we maneuvered through the hostile vegetation, but we did. Once through, we climbed up a small hill that led to the back of the temple.

The building was very big and definitely deserted. The walls were gray and dirty, as if they had been rinsed and stained continuously by black water. The area around the temple was completely overgrown, and the stone gate that stood in front was doing its best not to fall over completely.

I could hear parrots cackling to one another from the vine covered tree canopy, but even when I craned my neck to look up at them, they were too high up and too camouflaged amongst the green leaves to be seen.

We noticed two Indian men standing about in the dilapidated courtyard as if it were the most normal thing to do. Cigarettes dangled from their mouths, and they stood about scratching their heads and murmuring to one another in Kannada. They were wearing the usual dress of the Ganjam village men–plain, cotton sarongs which they tied about their waists and folded in half just above the knees.

They did not appear to be surprised to see us, but then, there was nothing odd about that, since it did not seem likely that these two fellows could find anything surprising given their cow-like expressions.

Of course Radha Kanta overlooked this particular aspect of their personalities and sauntered over to them with purpose.

“Hello!” he said, adopting the funny accent he used when he spoke to Indians, as though that would help them understand his english better. “What is this place?”

No response.

He put his hands on his hips, contemplating the temple. Then he turned back to the two men. “Me and her are going inside to look, okay? You please watch our bikes. Make sure nobody steals them.”

I gaped a little as he placed our bicycles in front of them and started off toward the temple entrance. I ran after him, wondering why he was so crazy.

There turned out to be no door to the temple, just a hole in the wall. Radha Kanta gingerly poked his head inside. I stepped next to him and peered in. There appeared to be nothing in the room except an impenetrable blackness, big piles of bird guano, and little shapes all over the ceiling. Our eyes strained in the dark, and I began to make out strangely shaped holes in the walls. They seemed to be intricately designed windows, but there was no light coming through them. I concluded they must have been filled in with bricks.

We kept looking around, but neither of us volunteered to step inside. I noticed a small opening in the back wall that seemed to lead to another room. A faint red glow was pulsing through the blackness from that back space. But before I could form any thoughts about what might be glowing red in the dark, something bit my leg.

“Ow!” I shouted. I felt another bite, and then I was being bitten all over. I jumped up and down looking about wildly. Red ants were swarming around the floor and up my legs. “Oh my god! OW! Red ants Radha Kanta! They’re biting me!”

I wonder to this day if he even heard me. His head was still stuck in the dark, poop-filled room and he was talking excitedly to the empty space I had previously occupied. Some part of my brain registered the fact that he wasn’t getting bitten at all, and I suppose I was envious of him, as I hopped about, brushing ants off of me. I wanted to scream.

Once I had separated myself from the blood thirsty ants and all of their relatives, I grabbed Radha Kanta’s arm. “Let’s leave now. I want to go.” Luckily he seemed as eager to leave as I was. We returned to the two stupefied Indian men and grabbed hold of our bicycles.

“How can we get back to Sri Rangapatna?” Radha Kanta asked them. Sri Rangapatna was the name of the village we lived close to.

For some reason they actually answered him. They pointed to the road in front of the falling-over stone wall and said, “Sri Rangapatna, that way,” with the perfunctory head bob the Indians always use when they speak.

We turned to see where their fingers were directing us. The road split into three parts.

“Which way?” Radha Kanta asked.

They smiled happily, and one of them said, “Yes, yes,” flashing his head-full of yellow, crooked teeth.

I sighed and together we left them to their cigarettes. We stood out on the forked road. “Left, right or straight ahead?” I asked no one in particular.

“Well…” Radha Kanta furrowed his brow.

I looked in one direction, seeing what lay along that road. “Wait a minute…” I said.

Radha Kanta paused his brow furrowing and followed my gaze.

“Let’s go down this road, because I think I’ve been on it before,” I told him.

We started down that way, examining everything around us, in hopes of spotting familiar landmarks. I wondered if we’d ever make it home, or whether we’d just be found as skeletons on the side of the road.

Each minute stretched longer than I had known a minute possibly could stretch. But slowly, very slowly, recognition creeped in on me, and before I knew it, I was riding along a completely familiar roadway. “This IS the road!” I yelled.

“What?” said Radha Kanta.

“I know where to go from here!” I told him. “We’re not lost!”

Radha Kanta whooped in relief and we pedaled with a new-found enthusiasm. We recognized a side path to turn onto and soon were well on our way back home. Radha Kanta gave me an appreciative smile. “I’m so glad you were with me Tulsi, ‘cause I would never have known which way to go.”

I grinned.

Suddenly every bush, every tree, every cow even, was familiar. We were both so relieved we could have wept. The final stretch home went by so fast, it seemed to be only minutes before we were standing back at the front gate of Govindaji Gardens.

We threw the bicycles down and ran to my house, where we began to gulp down glassfuls of water.

Our siblings surrounded us, asking us where we had been and what had happened. We told them we’d gotten lost and related the whole story.

At the end, Radha Kanta, evidently carried away with the afternoon’s excitements, added, “Yeah, and as we were riding away from the temple, I saw a white thing fly out of the roof! It was wearing a big cape and riding some weird creature.” His eyes were wide, and he looked at each of us in turn.

I stared back at him. “You did?”

“Yes!” he cried. “Swear to god I did!”