(names have been changed for the characters in this story, to protect their privacy, FYI)

“My loves!” he cries, as he rollerblades into the Laleeta Indian Restaurant where we are sitting. We stand up, laughing at the sight of the rollerblades strapped around his ankles, and the disconcerted glances from the Indian waiter and south African customers at the table near us.

After embracing each of us he glides into a seat across from us, where the vegetable curry and rice we ordered for him is waiting.

The first time we met Tom Peterson was over 3 years ago, when Addison and I were riding our bicycles across the United States and the 3 of us (4 counting Tom’s girlfriend at the time, Layla) ended up staying with the same Warmshowers host in Santa Rosa Beach, Florida. We didn’t know what to make of Tom at the time, but we ended up cycling all the way to Baton Rouge, Louisiana with him. He raised the camaraderie and comedic factor for us during that month of travel.

He had lived on in our memories as an eccentric, bicycle racing cheapskate, who would fill his empty taco bell bag with the free condiment packets from their counter spread, horde wet wipes from the Walmart dispensers to use later on to clean out his tent when we would set up camp, and who would compare the caloric value of the three different bags of 1 dollar trail mix at the Family Dollar, to make sure he was getting the most calories per dollar spent.

But it seems that perhaps Tommy Peterson’s days of hoarding free condiments and seeking out free or under $1 meals has come to an end for the time-being. Here in Brooklyn, he tells us, he’s started a loft-bed installation business and business is booming for old Tommy Petes.

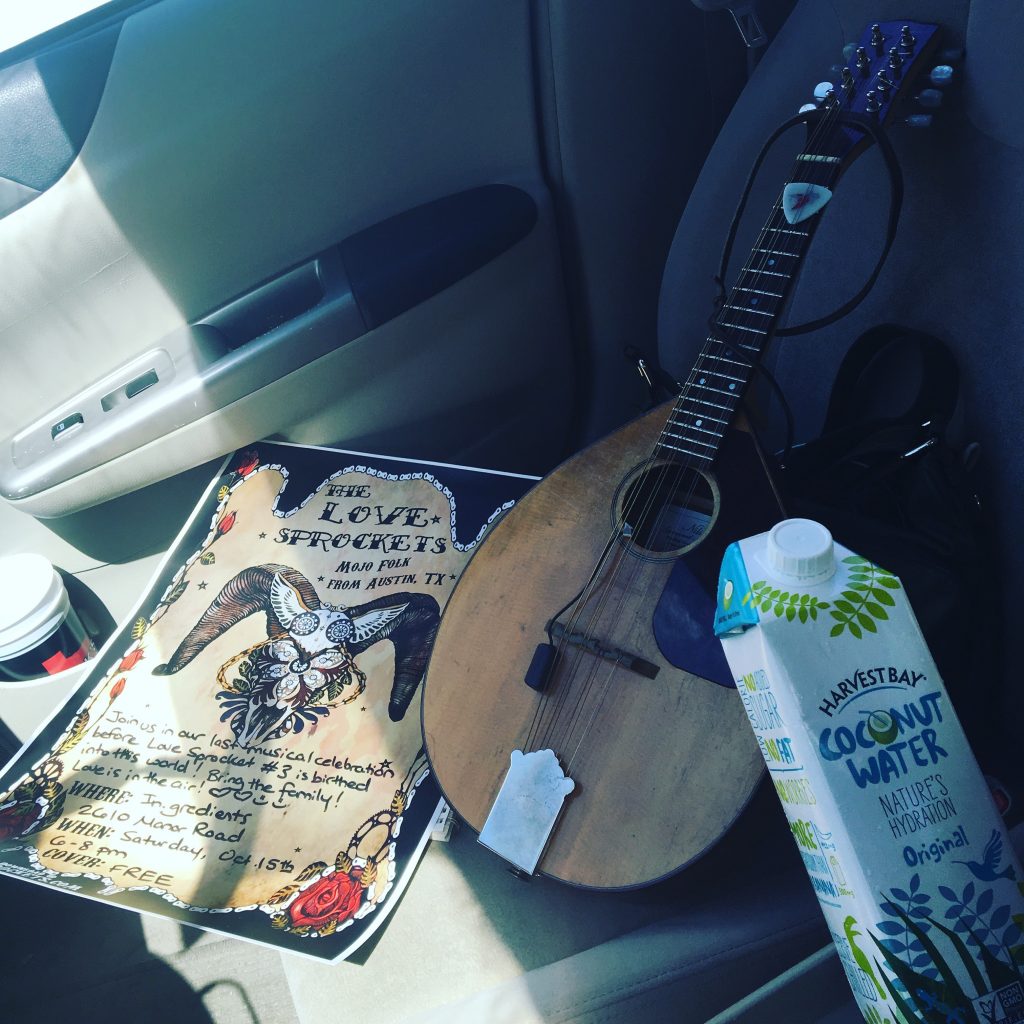

He pulls his lumber and supplies around with his racing bike and custom designed cargo trailer, and has more work than he could hope for.

He pulls his lumber and supplies around with his racing bike and custom designed cargo trailer, and has more work than he could hope for.

As if he didn’t have enough going on already, he works at a bar every Sunday night (“for the Pina Coladas” he says), working the bar or racing out on his rollerblades to deliver food around the city. When it’s a slow night he can host his business meetings at the bar with potential loft-bed clients.

Tom doesn’t seem to say ‘no’ to work when it comes his way, even when it appears in a bizarre and perhaps disconcerting setting. And as we have come to learn, Tom is a master at attracting bizarre and disconcerting events to him.

“Yeah I’m actually remodeling a haunted house around the corner from here,” Tom tells us, in between bites of vegetable curry. He orders a mango lassi from the waiter who appears every 10 minutes to refill our water glasses.

Addison raises his eyebrow, intrigued. “Haunted house?”

“Yeah, it was built in like the 19th century. I met this lady the other night on the street corner when I was eating watermelon…” he begins.

It was 1 am, a warm night in early July, and Tom had ended up working late on one of his installation jobs. He was exhausted and dehydrated, and decided a big slice of watermelon would do him good. He pedaled his rig to a nearby convenience store and purchased a watermelon quarter and a coke. As he hunkered down on the sidewalk to eat, a woman with a pitbull walked past and said to him, “Watermelon. Nice choice!”

He thought so too, until he was a few bites into his piece and discovered that his particular hunk of watermelon had not been laid down in the ice properly and was warm and soggy from a long summer day. He contemplated the piece for a moment, then put it down, having lost interest. The same woman who had passed by him a moment before circled back around.

“Are you going to finish that?” she asked, pointing at his watermelon.

“Nah,” he said.

“Mind if I have it?”

“Knock yourself out.” He handed her the piece.

She and the pitbull settled down next to him and she began to tear into the watermelon like a wolf ripping into a fresh elk kill. Soon the juices were flowing down her face and neck, soaking the front of her shirt.

The scene made Tom feel a little queasy.

“What’re you working on?” the woman asked between bites, indicating his cargo trailer.

He told her about his loft-installation business.

“Do you do any other kind of carpentry work?” she asked.

“Yeah,” he shrugged. “Anything, really. I’ve remodeled alot of houses, helped build others, pretty much whatever.”

He found out her name is Kathy, and she lives in a really old house nearby and would he be interested in doing some work on it. He said sure, why not.

After some time had passed, Tom told her it’s late and he needs to get to bed. They exchange information, but as he was beginning to walk away, she noticed that he was headed in the same direction as her house.

“My place is on this street,” she told him. “Do you want to step inside to see it yourself for a minute?”

“Sure,” Tom said.

The house was everything one could hope for in an old, historic building. Grand, grimy, and perhaps inhabited by generations of the dead.

Kathy showed him in and walked him around, telling him about her various project ideas. Most of them didn’t really make sense as far as what physical reality would dictate, but Tom humored her and heard her out. She seemed to be particularly obsessed with the stairway, asking him to do things like completely block them off so the upstairs was separated from the downstairs, or to level them and build a trap door.

She told him to follow her, and he noticed that as she was walking upstairs past a room on her right, that she waved to someone who must have been in there.

“Good night,” she said to whoever was in the room.

As Tom followed her, he glanced into the open door of the room where she was looking. A young girl was sitting on the bed, her eyes rolled up in her head. She began to convulse before she fell back into the bed.

Tom stared from the girl to Kathy, but Kathy gave no other indication that the girl was even there, so he stayed silent and continued up the stairs.

He waited for Kathy on the landing while she changed out of her watermelon soaked clothes. She reemerged from her room wearing a sheer, flesh-colored, silk suit. Tom tried not to notice that her outfit was completely translucent, but rather focused on the numerous photographs of a dead bird that she had laid out on her bedroom floor.

“It happened last week,” she told Tom. “The bird flew right up next to me. It paused in mid-air and we made eye contact. It’s like it was hypnotized.”

Her pitbull had taken advantage of this strange and marvelous occurrence, by leaping up and ensnaring the bird in its jaws. The photos Kathy had taken of the bird over the next 3 days showed that the bird had been torn to pieces, its entrails draped across the deck in a gruesome collage of death.

She had photographed the dead bird at night, in the morning, in the late afternoon, at different angles, with different lights and shadows that she had created to capture the manifold looks of its carcass.

Everytime Tom was deciding it was time to leave, she would entrance him with another story, another painting, another piece of art with an intriguing story tied to it, and he felt like a captive witness to this empty shell of a woman, who had so much to say, so many stories to tell, but who seemed to be sucking the very life out of him with each memory she shared. He could sense that the real person, the spirit of this woman’s body, was there somewhere, floating nearby, but she didn’t seem to be an active participant of her own life.

Her next wardrobe change was into a sundress that she pulled up just below her breasts. Tom was kind enough to pretend not to notice that she was naked from the top up. He was well and truly ready to head home at this point, when an incredibly angry man came thundering up the stairs.

“Where’s my drugs?” he was screaming. “Where are they? I’ll kill you, I’ll fucking kill you!”

Tom did not know where the man had come from, but he decided the best plan of action was to move slowly and to act calm. His escape route would have been down the stairs and out the door, but the angry man was currently blocking the stairs. Tom casually reached into his backpack and found a chisel, which he slipped into his pocket.

Apparently the man’s name was Jim, and he was a house guest of Kathy’s. She and Tom both assured Jim that they did not have his drugs, and suggested that he keep looking. But that they were most certainly not upstairs.

Jim thundered around, breaking things, cursing, and generally expressing his displeasure at having misplaced his drugs. But eventually a silence fell over the house, and Tom heard a click and a deep puff, and knew that Jim and his crack pipe had been reunited. Peace settled in, and Jim was soon apologizing for his behavior.

A strange dance began to take place, which continued to imprison Tom at the house. Jim would start talking about Kathy, telling Tom unpleasant stories and bits of information about her, and Kathy would get angry and leave, not wanting to have listen to it. When Jim would finally leave Tom alone for a second, Kathy would reemerge and demand to be told what Jim had told Tom, and then she would respond with a deluge of unpleasantries about Jim. When Kathy disappeared Jim was back, and the sequence would continue.

It was around 5 am when Tom was finally able to extract himself.

“And you still ended up working for her?” we ask him, incredulous.

“This woman had cash just falling out of her pockets,” Tom says defensively. “Someone’s gotta scoop up the cash!”

So Tom started his first project there, which was dealing with the effects that some rotting beams were having on the door frame and stripping. It was his third day at the house, and he had just done some glueing around the door frame and was waiting for the glue to dry.

It was a 95 degree day in Brooklyn, and the house had no A/C. He had been working there since 8 am that morning, and now it was nearly 1:30 in the afternoon. He was afraid to drink the water in the house, for reasons he could only attribute to the half-rotted, moldy aspects of the walls and framing. Feeling drowsy and dehydrated, and drained of energy in a way only this house and Kathy could make him feel, he lay out on the living room couch and drifted to sleep.

“Weh weh meh meh meeeeeee!”

“Hum hum hum hum…”

“Ugh, grrrrr, hmmmmm.”

Tom slowly opened his eyes, not daring to move. He was hearing people in the house, and none of them sounded very friendly. He listened for a while, and was able to discern six different voices. As far as Tom knew, the only person home was Kathy, and she was upstairs.

One person sounded like he was angry, with a deep voice that reprimanded another person, who responded with whines and whimpers. The other voices were talking amongst themselves, though Tom soon realized that he could not discern what any of the people were actually saying.

This may be the end of Tommy Peterson’s adventures, he thought, as he felt his limbs seizing up with an undefinable terror. He was immobilized. He could do nothing more than lie there with his eyes wide open, listening to voices as they got closer and closer.

Something caught his eye at that moment. It was a foot, stepping backwards onto the second-to-last step of the stairway that led to the upstairs. It was followed by a second foot, which ascended onto the final step, also facing backwards. The legs of the person were moving in a stiff, robotic way.

A silent scream was trapped in Tom’s throat. Then he saw that it was Kathy. She stepped into the living room, still walking like a backwards moving robot. The voices had narrowed down to two or three at this point, but they were all coming out of her mouth, and none of them sounded like her own.

As she turned around, her body seemed to relax and with a small convulsion, she was falling into a normal, forward moving gait that was completely unlike the robotic one she had been using before. When she saw Tom, she said, “Oh, so did you finish glueing the trim?” in her own, single person voice.

Tom sat up, gasping in confusion. “What… What do you mean??”

But he could see that as far as she knew, nothing out of the ordinary had happened, and he was forced to regain his composure without receiving any kind of explanation or acknowledgement of the bizarre event that had just unfolded in front of him.

At the point in the story when Tom had mentioned the backwards foot making it’s way robotically down the steps, I had shrieked in horror and flung myself into Addison’s arms. As I squeeze him even harder I also laugh in disbelief.

“Did you tell her she was walking backwards down the stairs like a robot and speaking in six voices?” I ask.

Tom shrugs. “Nah, I didn’t want to freak her out. She’s pretty paranoid as it is.”

Addison is shaking his head. “And you’re still working there?”

“Yeah,” Tom says, and now we are all laughing.

But I guess maybe there was a good reason why she wanted those stairs blocked off.