“FUCK YOU!!” I scream, rain pelting my face and filling my mouth. “I’m trying SO HARD, so FUCKING hard. FUCK. YOU.”

A semi truck passes me on the bridge and a wave of dirty water splashes over me. I don’t care. I’m soaked through anyways.

I am crying now, gulping and gasping, my tears mixing with rain.

When I finished crossing the bridge, I pull my bicycle over. The front tire has been losing air slowly and has become quite soft. So I yank my hand-pump off the frame, and kneel on the wet ground while I fill the tire with more air. I shiver as my wet clothes cling to me, and a peal of thunder cracks the bruised sky.

I had left Dzitbalche that morning, a small town about 50 kilometers from where I was kneeling in a puddle now. I had awoken quite early, without prompting from my alarm, and had meditated sitting on the square lump that represented a bed at the hospedas I was staying at. I had slept on top of the covers with my sleeping bag, not daring to venture into it’s depths after discovering toe nail clippings on the blanket.

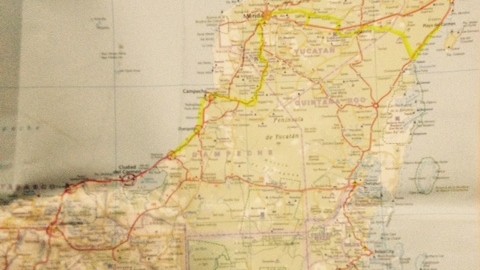

I hadn’t meant to end up in a hospedas in Dzitbalche when I had ridden out from the city of Campeche on Friday morning.

I had intended on cycling to Calkini, a halfway point between Campeche and Merida. Merida was my goal, my shining portal of light, a beautiful city with two beautiful warmshowers hosts who had a room waiting for me, a place that was not a hotel, had internet connection, a washing machine, bicycle repair shops, and people who speak english.

I had pulled off the highway on Friday afternoon after having traveled about 80 kilometers that day, to ride on a side road into Calkini. Within moments I received a flat tire from some broken glass, or maybe shards of wire that decorate the sides of the roads here like confetti.

Unfortunately I was not aware of the flat tire until moments later, when I went over a surprise speed bump a little too fast, and felt the unmistakable *whump*–the sickening sound and feeling of a flat tire that is even more flattened beneath a mountain of gear.

I pulled over right away, avoiding the flabbergasted expressions of the villagers who were walking past me, or leaning on their shovels, their work forgotten due to my unexpected arrival into their usually cycle-tourist-free existence.

Don’t they have work to do? I thought grumpily, wishing everyone would just go away while I surveyed the damage of my only mode of transportation, my house-on-wheels.

“Mi bici es mi vida,” I always tell people, when they talk to me about my strange, overloaded vehicle. My bicycle is my life.

Well, my life was currently looking a little butt-fucked, if you don’t mind me saying.

Not only was my tire completely flat, but as I was pumping it back up so I could at least creak my way to a place to sleep that night, I noticed I also had broken a spoke.

Cue the doomsday music.

After filling the back tire with more air, I gingerly remounted my injured steed and began to roll slowly down the streets, hoping to see a sign for a hotel of some kind. When I reached the center of town, I pulled over to look at my phone map, and an old timer sitting on a bench yelled over to me.

“Que estas buscando? A donde vas?”

Well if he was asking me what I was looking for and where I was going, clearly he wanted to help.

I pushed my bicycle over to where he sat and asked, “Sabes donde esta un hotel?”

“Si, si!” He went into a lengthy description of where a hospedas was, telling me where to turn and what the landmarks were. I was a little nervous because it sounded like it might be hard to find.

But I set out to look for it, after thanking him and saying good bye.

It turned out the hospedas was actually quite close and easy to find, and when I pulled up, two older gentleman leapt up to greet me and help me bring my bicycle inside the courtyard. They were amazed to see me and my gear, and asked me lots of questions about my trip.

“Tiene un cellular,” one man said, pointing at my cellphone mounted to my handlebars.

“Asi que se puede hablar con su novio,” the other said, chuckling. (‘So she can talk to her boyfriend’).

“Mi promitido,” I corrected. (‘my fiance’).

“Oohh!” they gasped appreciatively.

It’s somehow even more impressive to the Mexican people that I’m cycle touring alone AND I have a fiance.

That night one of the guys took me around town to visit a couple of bike shops, both of which where closed. But we were told one of them would re-open at 5 pm, so after taking a shower, I headed back there, again assisted by the older man who carried my wheel for me.

A bicycle shop in Mexico is not a bicycle shop in the United States. The ones I’ve seen look kind of like auto shops in the U.S., just smaller, darker, and even dirtier, if you can imagine that. They usually have a few rusty mountain bikes lying around, and it always makes me wonder what exactly they’re doing to improve the bicycles they work on.

The mechanic took my wheel and surveyed my broken spoke. I also told him I had a flat tire and could he fix it.

“Si, si. 30 pesos. Volver por la manana.”

Come back in the morning? Hmmm… I had almost 100 km to ride to Merida in the morning, I couldn’t be hanging around waiting for his shop to open.

“Voy a Merida con mi bici en la manana,” I explained.

“Ah ok,” he said. “Entonces, volver en una hora.” (‘Than come back in an hour’)

I was relieved.

Wow, I’m not screwed. This guy’s gonna replace my spoke, patch my tire, and I’ll be good to go tomorrow!

Me and the older man (he did tell me his name, but unfortunately I can’t remember it) stopped and got tacos (he didn’t eat, but insisted I order 5 or 6–I thought maybe they were kind of small so I finally agreed to order 5 and had to take 3 to go when I discovered they were of normal size).

When we returned to get my wheel, the mechanic waved at it sadly.

“No puedo.” He couldn’t fix the spoke because he didn’t have the right tools for taking my cassette off.

My heart sank.

He did show me that he had kindly filled my tire with air.

I knew this meant he hadn’t actually patched the tire, so that was something else I would need to do before going to sleep that night.

It was difficult to remember to smile when morning came.

I had patched my tire but it was flat again, so I just replaced the tube, not feeling patient about finding a potentially microscopic hole in addition to the other one I had patched.

I pulled my bicycle outside of my room and into the center courtyard, where the older man from the day before saw me and came over.

I was trying to put my wheel back on after having changed the tool, but it was a little complicated because of being the rear one and dealing with the chain and gear shifter. The man was trying to help me–though I really did not need or want his help–which almost made matters worse. Once I had the wheel in place, I noticed it was rubbing the brakes on one side very badly.

I knew this was because of the broken spoke and the wheel not being ‘true’.

I couldn’t explain this in spanish to the guy trying to help me, so he kept fussing with it, though he seemed to know about as much about bicycles as I do about engineering.

I called Watson and he talked me through, so that I could at least set the wheel up to a balanced enough spot where I could ride with the brakes released.

I finally had to shoo the overly helpful guy away. “No mas. No mas!” I said, as he continued to finagle and fuss hopelessly.

I think I may have offended him because he walked away and did not return.

But I was relieved to have him gone.

Fighting back tears, I set the wheel, turned the bicycle right side up, and loaded it with my gear.

As I was rolling out of town, I noticed the other bicycle shop was open.

Hmmmm… I thought. Maybe they have the right tool for taking my cassette off and they can fix my spoke!

The potential promise of my 100 km ride to Merida with all of my spokes caused me to stop and talk to the guys at the shop.

Maybe it’s just because I’m from the United States and in Mexico the culture is very different, but I made the assumption that by explaining to them that I had ridden to Dzitbalche from Austin, TX and was on my way to Brazil–and needed to ride all the way to Merida today–that somehow they would ‘get’ it.

I assumed they would see my enormous, heavy pile of gear and think, “Well gee. This girl is carrying a lot of weight and has a long way to go today. Let’s make sure we take good care of her and her bicycle so that she gets there safely.”

But sadly, this was not the case.

Despite my insistence that the removal of the cassette was the potential barrier to them fixing my spoke, they didn’t look closely and just told me to take all of my gear off my bicycle so they could work on it.

Sure enough, they took the wheel off and began to try and remove the cassette–with no luck.

One of the guys seem to fiddle around with the wheel and the spokes, as if he may have been truing the wheel. I could only hope.

Then he gave me the final assessment. They couldn’t fix my spoke because of the same damn thing the other guy ran into–they couldn’t take the cassette off.

I watched with growing dread as they tried to put my wheel back on.

Why did I let them touch my bicycle? Why was I so hopeful? I could have just ridden past, and saved my self the trouble…

I finally stood up and told them to get out of the way.

I finagled with my wheel until I had found a good position for it to spin freely.

I reloaded all of my gear once again.

I thanked them… for trying I guess… and tried to ride away.

But my wheel was wobbling horribly.

An old lady being pushed in a strange bicycle cart thing by a man rolled past me and she asked me where I was traveling to.

I tried to answer her, but I was so upset by my wheel that no words came out.

She shook her head at me and continued on.

I turned back to the ‘bike shop’ and told the ‘mechanic’ that my wheel was worse off than before. As he watched me slightly open mouthed, I frantically grabbed a small log from their shop and hoisted the back of my bicycle on it. I indicated for him to hold the bicycle in place for me. Than I began to spin the wheel and try to assess what else had gone wrong.

The other ‘mechanic’ came over and eventually ascertained that they had not actually tightened up my wheel bearing properly after having loosened it to try and get the cassette off. He grabbed a wrench and tightened it. Seemed like an obvious thing to have done in the first place, but hey, it worked as an afterthought as well.

Finally, I was able to ride away without any undue wobbling or rubbing.

That’s right around when it began to rain…

“Do you know what?” I said out loud to my bicycle, watching droplets of water drip off the front of my helmet. “You are the most awesome bicycle I have ever owned. And guess what? You and me, we’re going to Merida today! We’re going to stay with a nice couple named Ken and Erin, and we’re going to take really good care of you once you get there. All you have to do is just hold out for today. I promise I’ll get you all fixed up in Merida.” And then, to my surprise, I began to cry and say to my bicycle, “I love you. I love you so much.”

Well, yes, I suppose I had gone a little batty from riding alone for so long and being worried about getting stranded on the side of the highway with my bicycle and gear.

As my my mind raced around, assessing potential problems of riding with a broken spoke, and coming up with solutions just as quickly, I saw some beautiful yellow flowers growing along the roadside.

I remembered something I had read in one of Thich Nhat Hanh’s books: “Happiness is always possible in the present moment. The flowers are keeping your smile for you. You can have it back anytime.”

A smile came to my face.

So it is that I find myself 50 km to Merida, in a full-on downpour, kneeling on the side of the highway and pumping up my front tire.

I continue on down the highway, until to my relief, I eventually spy a bridge that I can hide under.

I pull under the bridge and begin to assess the damage. I had been so intent on riding as quickly as possible to Merida, that I had not taken great care in insuring my electronics were in waterproof containers.

My ipod has shut down after getting wet in my belly pouch, and my phone and extra charger are in danger of meeting the same fate.

I quickly wrap them in some clothes from my dry-bag pannier and stow them away into safety. I pull off my dripping wet over-shirt, shivering gratefully as I get my coat out and put it on. While I wait for the rain to pass, I eat an apple and just pace back and forth beneath the bridge, trying to stay warm and keep my limbs moving.

15 minutes later, I’m able to keep riding, though there is a steady drizzle still oozing out of the sky.

When I finally arrive at Ken and Erin’s house in Merida, it is 6 pm, and my feet are sloshing in my shoes. Ken shows me inside his magnificent home and to my room. Than he leads me to the kitchen. “Are you more wet, or more hungry?” he asks me.

I feel like I can barely stand up. “I’m honestly not sure…” I say, squelching alongside him. “But I think I’m too hungry to get changed.”

I eventually resign myself to at least taking off my wet shoes and socks, putting dry socks on, and then settle down in front of a giant bowl of homemade chili.

“You have no idea what it means to me to finally be here,” I tell Ken later that evening. “Today was a true trial. Thank you so much for being here to receive me.”

Later I go to say goodnight to my bicycle. “Hey,” I whisper to her, avoiding the puddles of water that have formed around the floor beneath her. “You did it. You fucking did it. You are so amazing.”

And true to my word, I did get her all fixed up over the next couple of days. The bicycle mechanic in Merida had no problem removing my cassette, replacing the spoke, and truing the wheel, charging me a whopping 30 pesos for the whole operation (that’s like $1.50).