I am a dead body moving

I’ve got lightning in my hands

I won’t be here for long

So you’ve got to understand

You can dance with the demon

Look him dead into the eyes

I’ve already been where we go

When we die…

Now, when I sing this song, it seems to fill the air with the intensity of my feelings for her.

How many times had she heard us play that song?

Was it she who taught it to us?

I remember when we first started learning the song, in a second story apartment in Mexico City. Our veranda doors were wide open, and the hot, sunny, taxi-filled air blew in over us, a wash of street taco smells, and vendors selling things made out of plastic in all shapes and sizes.

I had ridden my bicycle halfway across Mexico by this point. When Addison had arrived at the Juarez International Airport, I held onto him like a lifeline in a tumultuous ocean of fears, hopes and dreams that seemed to be hanging just above me, ready to be dashed against the rocks at any moment, should he ever stop loving me.

During the months leading up to this moment and even while we were together, I cried more than I can ever recall, crying as though my tears were prayers. I cried until I was dehydrated, until my nose bled, until I felt drained of life, and then I would cry some more at the miserable human I had become.

She came to me at my darkest moment, an answer to my prayers. She loved me so intensely, that I was able to draw her to me in my time of need.

We learned this song, Dead Body Moving by The Devil Makes Three, during our short stay together in Mexico City.

Then Addison flew home to Austin, and I crammed myself into a bus, holding onto Nana as long as I could before it took me away, across to the Southeast, to Villahermosa, where I would continue pedaling in a loneliness that felt desolate.

But from that time on, I was never truly alone.

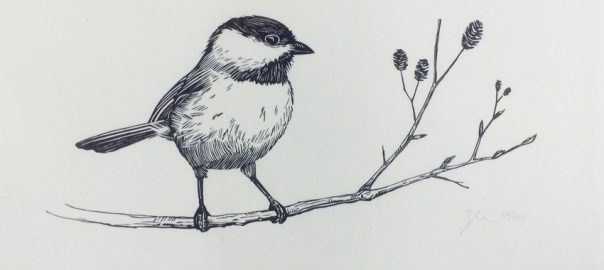

Nana had tattooed a chickadee onto my leg, and I invoked its fierce spirit to join me on my journey.

I didn’t know that she was with me, but I suspected, at moments, that someone was there.

I sing a ragged and a crooked song

The sun is setting and it won’t be long

My body’s weak but this soul is strong

I am a shadow dressed up in these skin and bones.

I am afraid to regret.

Afraid to regret that I didn’t treasure the 9 months I had with her more.

How could I have known?

How can we ever know when the last day is we will get to be with our loved one?

It was only hours before I was to go into labor. Watson–Uncle Watson, as we thought she would learn to call him–had stopped in to visit.

“I can’t believe there’s a baby in there!” he cried, staring at my huge belly with a mixture of awe and deep suspicion.

“Do you want to hear her heartbeat?” Addison asked. He wore an expression of pride only a father can wear. She was his baby, he’d helped to make her, to keep her alive this long.

Addison pulled out the doppler MariMikal had lent us that day. “Our midwife sent us home with this doppler so we could check her heartbeat. She hasn’t been moving as much since Saturday, so we were a little worried.”

He lifted my shirt and put some goo on my belly, than pressed the doppler where her heart was. It took a second to find the right placement, but then we heard her heartbeat pulsing out through the little speaker, the greatest proof of her aliveness.

“Holy shit,” Watson said with reverence.

Then we picked up our instruments and surrounded her with music.

Dead Body Moving was the last song we ever played for her while she was still alive.

We weave our stories in a worthless yarn

Trying to escape with all these tricks and charms

It’s far too late to ring the alarm

We are just babies falling in the spider’s arms.

There is a kind of shock that takes over, before devastation settles in.

The next morning, when I went into labor and my midwife came to get everything ready, I refused to believe that anything was wrong after she checked for Chickadee’s heartbeat and heard only silence.

I refused to believe that her lack of heartbeat meant death.

It wasn’t until I heard the rasp of panic in my midwife’s breathing, while we rushed through the hospital hallways, that I began to acknowledge that something was terribly wrong.

“There is no fetal heart activity,” a doctor with a strong Australian accent announced to us. The sonogram clearly showed her little ribcage, her little heart not beating.

Addison recalls a nurse handing him a pile of paperwork to sign, seconds after being told his little girl had died. He said he discovered in that moment that he no longer knew how to read. Our midwife snatched the papers from his hand. “Go to her!” she said, and he made his way to my side, held my hand, and laid his head in my lap to cry.

We went home, and I continued the long day of work that stretched ahead of me.

Giving birth.

I’d never thought about how someone could die before they were born.

It’s all backwards.

How is it that you can still be born even though you’re dead?

Chickadee managed it. She’s about as determined as her mama.

24 hours later, when she finally emerged, I could let myself fall apart.

The way her arm fell limply behind her when the doctor handed her to me, said it all.

And yet I still felt a great relief and joy to be able to hold her in my arms finally, to be able to give her to Addison and see him hold her for the first time.

Why did she have to be so perfect?

Why did she have to have Addison’s eyebrows, his shock of thick hair, my hands and feet?

What was the purpose of all of this?

My father and sister arrived from their separate ends of the world, having traveled all night from Washington and Idaho. It was 5 am when they found us in the dark hospital room, a warm spotlight shining down on our new family.

How strange that the newest family member had decided to leave us so soon.

We all wept together, and laughed at how big she was. I’ll never understand how I fit all of that baby inside of me, and how I ever managed to get her out.

And then there’s the anger.

9 months of preparation, feeding her, learning about her, buying things for her, receiving gifts on her behalf, making plans for her life, practicing spanish and french so she could hear other languages in the womb, discussing what she was going to look like, what musical instrument she might end up playing, how beautiful she was going to be…

Why?

When someone tells me it happened for a reason, that she chose to leave for a good reason, than I feel as though the world is a stupid, shitty place full of stupid, shitty people and we’d all best just get to it like the Buddha did so many hundreds of years ago. No point in wallowing around here for much longer. Enlightenment is the only worthy pursuit.

And if she chose to leave, than how could she? How could she do this to me?

But than there’s always the option that there is no why, there is no reason why she died, that she didn’t want to leave, that things are random, and shit happens.

And that makes me feel like the world is a stupid shitty place full of stupid, shitty people.

Except that we’ve been showered in so much love by all of the people we know, and even those we didn’t know that we know. Cards have come in the mail, flowers, food delivered to our door, long hugs, sympathetic smiles and shared tears.

Our family surrounded us and kept us afloat when we felt we would drown.

How could I ever have doubted that I am loved? How could I have ever believed that people are stupid and shitty?

We buried her 3 feet under, at a green burial plot out in the countryside. A handful of friends and family were there to dig the hole and to listen to us sing to her, to tell her story through tears, and to add their own voices with words and songs.

She was wrapped in her daddy’s flannel, the one he’d rode all the way across the United States with, the one with the patches that Peggy had sewn on for him in Florida, because even though it was full of gaping holes, he wouldn’t give up on it.

And she was wrapped in her mama’s green elephant tapestry, the one I’d gotten in India 10 years ago when my sister and I visited my brother there.

Her grandmother got her a stone chickadee statue to stand over her grave, and a rose quartz heart.

Her aunty Bhakta Priya and I hung a birdfeeder full of sunflower seeds near her spot, so she could be kept company by the birds.

I know she’s not just there, in that little grave. I know she’s everywhere, and I hope that she will never leave me.

For now I try to heal. My heart feels like a piece of pottery that fell, and broke, and I’m trying to glue it back together.

One day I’ll get all of the pieces back in place, but you’ll always be able to see the cracks.

And the song of the chickadee will always find its way through those cracks, and reach me.

“This body is not me;

I am not caught in this body.

I am life without boundaries:

I have never been born and I have never died.

Over there, the wide ocean and the sky with many galaxies all manifests from the basis of consciousness.

Since beginning-less time I have always been free.

Birth and death are only a door through which we go in and out.

Birth and death are only a game of hide-and-seek.

So smile to me and take my hand and wave good-bye.

Tomorrow we shall meet again or even before.

We shall always be meeting again at the true source,

Always meeting again on the myriad paths of life.”

― Thich Nhat Hanh, No Death, No Fear

ridiculously kind and generous. They brought us to a restaurant immediately after we arrived at their house. They took us to a store so we could get some warmer supplies [we’ve been pretty darn cold these past few days!]. They let Dagan buy a blanket, but insisted on giving me a sweater from their house, as well as a ‘tuk’ [a warm hat] for Dagan.

ridiculously kind and generous. They brought us to a restaurant immediately after we arrived at their house. They took us to a store so we could get some warmer supplies [we’ve been pretty darn cold these past few days!]. They let Dagan buy a blanket, but insisted on giving me a sweater from their house, as well as a ‘tuk’ [a warm hat] for Dagan.